My Sisters Made of Light

My Sisters Made of Light

A Novel by Jacqueline St. Joan--finalist, 2011 Colorado Book Award-Literary Fiction; Winner, 2013 Morrow Lectureship

"I started reading My Sisters Made of Light and could not put it down. It is a powerful story, well-presented, well-researched, and written with passion. The labor of duty became a labor of love. I read voraciously but have not come across a work which deals so effectively and skillfully with the cultural fault lines of Pakistani society." —S. Akhtar Ehtisham, author of A Medical Doctor Examines Life on Three Continents: A Pakistani View

Press 53, Winston-Salem, NC, 2010

(Price includes domestic shipping and taxes, if applicable.)

Update on the book:

Our love is bricks and mortar! THANK YOU again to all our donors and book purchases. Together we sent $25,000 to Pakistan for the construction of this shelter for women and children escaping abusive situations. The shelter opened in 2016!

Excerpt from My Sisters Made of Light

In 1958 the air was still sour with the stench of the slaughters that had occurred eleven years earlier when the British ran like dogs and India cracked. The blade that slashed the map also partitioned the bodies of the people, etching fear in their bellies and revenge in their hearts. Ten million people migrated. Lines and lines of Hindus from the Indus River Valley, in what would later be designated “Pakistan,” packed their lorries, rode bullocks, and walked, to cross the border into India. Lines and lines of Muslims from India carried all that they owned to be part of the new Islamic nation. Rioting occurred first in Calcutta and then spread to Punjab. The refugees scouted the routes to avoid one another in the passing. If a trainful of Hindus was murdered by Muslims from Lahore (and they were), then a trainful of Muslims would be murdered by Sikhs and Hindus from Amritsar (and they were). Entire families were butchered and their body parts were delivered by horseback to their villages. The people emptied baskets of breasts and pails of penises onto the ground—even the stubs of baby penises with scrotums like tiny figs. The soil was soaked with all the lost futures, and when it was done, when the trauma finally subsided to abide in the bodies of the people, they had to plant seeds in, and eat the fruit of, the same earth. Sikhs and Muslims alike knew the taste of each other’s blood well, and they kept to their own.

Kulraj and Nafeesa in London. Romeo and Juliet in Verona. A Muslim and a Sikh in Pakistan. All of history conspired against them, but no matter. They would find a new way.

Praise for My Sisters Made of Light

It's an important book, one that places a vital issue squarely on the table, makes it understandable and sympathetic, more than a sad fact of life in a far-away country. It's also a gripping read, hard to turn away from, hard to discount. Or to put on the shelf for later. The characters live and breathe; they are weak, brave, human; they can get under your skin and keep you awake at night. – Susan O'Neill, author, Don't Mean Nothing

In My Sisters Made of Light, Jacqueline St. Joan uses her extensive travels and research in Pakistan—as well as her own experiences as a human rights activist, lawyer, and judge—to share with readers a compelling, heartbreaking, and sometimes terrifying look into the lives of women and men in the social, political, and religious maze that is Pakistan. The novel centers on activist sisters who dedicate themselves to helping the women of Pakistan.

"Jacqueline St. Joan writes with the passion of a life-long feminist and the insight of wide experience. She brings to her story what she brought to the law, a conviction that life is full of both struggle and purpose and that grace comes to us when we have no reason to expect it." —Dorothy Allison, author of Bastard Out of Carolina

"My Sisters Made of Light is an exquisitely-told story. By weaving her far-reaching knowledge, experience, and imagination, Jacqueline St. Joan’s characters and settings bloom. Its narrative movement is simultaneously dynamic and delicate, deftly floating the reader through scenes, internal points of view, and an overall intriguing story that resonates in both the physical and ethereal senses." —Tom Popp, managing editor of F Magazine

"My Sisters Made of Light is the riveting story of Ujala, a Pakistani schoolteacher imprisoned in Adiala Prison, a women's penitentiary that holds the lives of hundreds of Pakistani women in limbo. Abused and lost, these women all have heartbreaking stories of the violence that lead them to imprisonment. With caution and devotion, Ujala slowly reveals her story to Rahima Mai, the Women's Prison Supervisor, forming a bond with the woman who may hold the keys to her freedom.

Book Reviews:

Special to the Denver Post "My Sisters Made of Light,"

by Collen O’Connor

When Jacqueline St. Joan traveled to Pakistan to research "My Sisters Made of Light," her novel about honor killings of women who shame their families, she stayed in people's homes, connected with human-rights activists and visited a women's shelter in Lahore.

But she went nowhere without a male guardian.

"You are considered to be fair game if you're not with a man," she said.

Women's need for protection can be acute in countries where violence against women is endemic, as it is in Pakistan. In her novel , she writes about three women who suffer the type of violence directed against real-life Pakistani women and girls — such as Malala Yousafzai, the teenager shot in the head by Taliban gunmen last year after she dared speak out in support of education for girls.

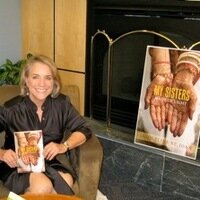

Since the book was published in 2010, St. Joan has spoken at more than 100 events hosted by libraries, book clubs, civic clubs and community centers across Colorado, and raised $19,000 to build a shelter in Pakistan for women with children who have no place to escape from abuse.

"Busy, professional women feel connected to these issues and care about these characters," said St. Joan, a Denver lawyer passionate about human rights. "That's one of the values of literature, that it can connect us to a world we don't experience because we don't walk in the shoes of someone on the other side of the world."

Two days after Malala made her first video appearance since being shot, St. Joan continued to convey the tales of violence against Pakistani women to people in Colorado.

She spoke at a book club in Cherry Creek — invited by Ellen Berrick, who met her at the book club of former state Sen. Suzanne Williams. St. Joan was a huge hit.

"She explained the laws and customs to us in a way that made perfect sense," said Berrick. "She's given so much of herself to this cause, and I really admire that."

It started for St. Joan more than a decade ago, when she was washing dishes in a Denver kitchen with a Pakistani teacher after a small gathering of women had just watched a film about honor crimes in Pakistan.

"I'd heard the term but didn't really understand it," she said.

St. Joan listened as the woman revealed her secret rescue efforts in Pakistan to protect women in danger of being killed for something as simple as looking at a boy.

St. Joan had long been interested in women's rights. She had worked as a lawyer, county judge, children's rights advocate and domestic-violence activist. She also taught "Women and the Law" at Metropolitan State University of Denver, and in 2002, the conversation included women in the Muslim world, which is how she was introduced to the Pakistani teacher.

"When she showed that film to a small group at my home, I felt a mix of both my experience with family violence as a lawyer, and also my experience when my own parents essentially turned from me when I had an interracial marriage in 1967," she said. "My parents didn't know to handle that, and it did bring shame on the family as far as they were concerned."

Over years of research, she studied cases like that of Mukhtar Mai, who was gang-raped on the orders of a tribal council as punishment for her brother, then 12, who was said to have offended a powerful clan by allegedly having an affair with one of its women.

To write about honor-crime trials in the Pakistani civil and Shariah courts, St. Joan immersed herself in the work of Azizah al-Hibri, a legal scholar at the University of Richmond who has written extensively on women's rights in Islam.

Honor killings are on the rise in Pakistan, having increased nearly 17 percent in the past three years: to 705 in 2012 from 604 in 2009, according to data from the Aurat Foundation, a women's advocacy organization in Pakistan.

To help, St. Joan is building a women's shelter in Pakistan with the help of the teacher she met a decade ago. Half the proceeds from book sales go toward the building fund. She is about $4,000 short.

"It will meet the needs coming from a variety of tragedies," she said. "Some women have been physically and emotionally abused for a long period of time, from beatings to burnings.

"Others could be accused of dishonoring a family or a community. A very precious life is in immediate danger."

My Sisters Made of Light Reading Guide

The questions and author biography that follow are intended to enhance your reading of Jacqueline St. Joan’s My Sisters Made of Light, a drama set inside Pakistan’s human rights movement, 1957 to 1994. My Sisters Made of Light follows three generations of a Pakistani family as they make their way through life in the political, social, and religious maze that is their motherland. This novel pulls readers into the fascinating, heartbreaking, and often terrifying world of honor crimes against women in Pakistan through the life and family history of Ujala, a dedicated teacher. When Ujala decides to follow the path for which her mother has prepared her, she goes a little crazy before she pushes aside fears for her own safety to help other women escape from the impossible situations.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS:

How does St. Joan’s use of alternating Ujala’s first-person narrative with the narrator’s third-person narrative from 1958 (when her parents met) and 1983 (when her mother died) affect your response to, and involvement with, the characters?

Nafeesa says she wants to return to Pakistan from London to say goodbye to Jameel. Her Aunt Najma opposes this and urges Nafeesa and Kulraj to stay in London. Why does Nafeesa insist? Why does Kulraj comply with her wishes? Are they brave or foolish to return? Why?

Nafeesa never tells her children about what happened to her in Shalimar Garden even though Kulraj thinks they are old enough to know. Would you tell your children? Why does Jabril Kazzaz agree that they should not be told even as adults? Do you think these children as adults may have “known” what happened on some deeper level? Why or why not?

Which sister--Reshma, Ujala, Faisa, or Meena--is most complex? Who is most straightforward? Which was your favorite and why?

Do you think that major male characters—Kulraj Singh, Jabril Kazzaz, Amir-- are “too good?” How will they manage to go on without the women in the family?

What image would you use to describe the structure of the novel as it moves around in time? A tree? A river? A circle? Did you find its non-chronological structure satisfying? Disturbing? Didn’t notice?

What does Rahima Mai’s response to both Yusuf’s bribe and to the escape plan reveal about her character? Is Rahima Mai better off without Ujala in her life?

What is the significance of the fact that Ujala decides to carry a gun?

How has reading this book affected the way you think about Muslims as a group? About Islam as a religion? Did you notice other religions in the novel?

What do the author’s Acknowledgements at the end of the book tell you about her? About Pakistan? As an outsider, is she qualified to write such a story?

How did you use the map of Paksitan and the Family Tree throughout your reading of My Sisters Made of Light?

One reviewer writes: “In her writing, St. Joan comes much closer to Kristof [Nicholas D. Kristof, New York Times columnist] than she does to [Stieg] Larsson, [author of The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo] though with a healthy dash of Harriet Beecher Stowe.” What do you think this reviewer means? Do you agree?

How does the novel affect your response to the social and political conditions in Pakistan? Do you find yourself being more understanding or more judgmental of Pakistanis and/or their leaders?

Were you unsympathetic to any of the honor crime victims—Bilquis? Khanum? Chanda? Nafeesa? Others?

Is Reshma, the oldest sister, an admirable character? What major factor changes her attitude in the course of the story?

Ujala recounts a conversation she had with Lia Chee: “American empire?” Lia said. She did not like to hear me call her country by the term the rest of the world used. “Now you sound like a fundie.” “Just a turn of phrase,” I said, “but ‘empire’ does signify something. You know what I mean?” Do you know what she means? How did you, as an American, react to Ujala’s calling America an “empire?”

Which visual images in the novel are the most memorable for you? Why?

How does My Sisters Made of Light highlight the conflict between the conservative and the liberal elements in Pakistani society? What role do class, religion, and ethnicity play in honor crimes?

Is My Sisters Made of Light a love story? a hero's journey? a social commentary? a political novel?

What do you find most disturbing/satisfying about the novel's denouement? If you find yourself imagining an alternate ending, what would that ending be?

What meaning, if any, do you find in the book’s title?