THE SHAWL OF MIDNIGHT

Published by the Golden Antelope Press, The Shawl of Midnight, is a standalone sequel to My Sisters Made of Light, Jacqueline’s first novel that explored a Pakistani family’s determination to educate women and defend human rights.

The Shawl of Midnight is a coming-of-age story, a family saga, and a hero’s journey set in Pakistan, India, and Kashmir. We pick up the story eighteen years later, following young Nafeesa into the depths of family relationships, surprising changes over time and distance, and how we might discover through our own pressures and actions what we are shaped by--exactly what we are made of, and where home truly is.

Half of the author’s proceeds will go to two humanitarian service organizations, one in Jammu and Kashmir, India and in Lahore, Pakistan.

*E-book is available on Barnes&Noble

Reviews About The Shawl Of Midnight:

“Jacqueline St. Joan writes with the passion of a life-long feminist and the insight of wide experience. She brings to her story what she brought to the law, a conviction that life is full of both struggle and purpose and that grace comes to us when we have no reason to expect it.” -Dorothy Allison, Bastard Out of Carolina

“The Shawl of Midnight is a remarkable work. I found myself as immediately taken with this book as I was with its predecessor My Sisters Made of Light. Its depiction of time and place, its evolution of character, are told with such convincing detail that it has the ring of truth. I literally read twenty pages thinking I had turned only one. The Shawl of Midnight is a compelling story that belongs in the annals of literature.” - Harry Maclean, Edgar Award-winning author, In Broad Daylight and The Past is Never Dead: the Trial of James Ford Seale and Mississippi's Struggle for Redemption

“An absorbing, inherently interesting, deftly crafted novel that will have a very special appeal and resonance with women readers, The Shawl of Midnightshowcases author Jacqueline St. Joan's genuine flair for originality, eloquence, and the kind of memorable narrative storytelling style that fully engages the reader's rapt attention from first page to last.” - Midwest Book Review

“St. Joan manages from the first page to draw the reader into this exquisite novel about sisterhood, coming of age and the ways women can cross generations, borders and cultures to weave from the tatters of oppression enduring fabrics of deliverance and justice.” – Susan Greene, the Colorado News Collaborative

“The Shawl of Midnight is a mesmerizing second novel from Jackie St. Joan that takes you into the frightful challenges and drama of gender crisis in Pakistan and India through the experiences of a family we know well from her breakthrough book, My Sisters Made of Light.” – Fawn Germer, author of Hard Won Wisdom and 8 other titles.

“A masterpiece, a finely embroidered story.” – Zahra D. Buttar, Ph.D., College of Southern Nevada, Departments of Political Science, Women’s Studies and Global Studies

“It’s clear that this is a work wrought from lived experience but more than that, St. Joan writes like she’s on a mission from God. The Shawl of Midnight is drenched with the casual details of one who knows the world of her novel intimately and who wants to touch the universal themes. A really timely and wonderful contribution to the human story. ” – Alexandra Fuller, author of Don’t Let’s Go to The Dogs Tonight

Jacqueline St. Joan is an award-winning poet, memoirist, essayist, writer of fiction and feminist legal scholarship. Her writing intersects the fields of law and literature with the voices of contemporary protest and reconciliation. She writes about history and family fictions; the abuse of women and inheritance of racism; the minds of children, teaching and learning; law and justice and literature; South Asia, gardens, birds. She has a law degree and a Master’s in creative writing. A lifelong feminist, she is a mother, grandmother, and a social justice activist with a voice. Learn more about Jacqueline.

Jacqueline St. Joan - jackiestjoan@icloud.com

Copyright © 2020-2025 Jacqueline St. Joan. All rights reserved. Site by KO Web Design.

Flash Fiction: "The Home Visit" published by The Ravens Perch

What you feel here is how it happened there. The grown son was in the garage tinkering with a car. He pretended not to notice me.

"Mississippi Goddam" was published in Valley Voices, a literary review of the HBCU, Mississippi Valley State University, in its special issue “A Sense of Place,” Spring 2022.

In Spring 1927, when Sol Bryson was seventeen, the sky opened up, thunder cracked and the rains poured all the water from heaven into the Ohio River, the Allegheny, the Wabash, the Tennessee, all the tributaries that emptied into the Mississippi as it ran narrow in the Delta, and mud channels pushed back, creating one moving monster of water and all that it carried with it—houses and trees, bodies and parts of all those things and more. Sol heard the cries and saw the red mud rising like the terror inside him. The water was rising so fast that their cotton field was becoming just a spit of land surrounded by water, a long finger pointing east. They all ran from it, they had to.

This memoir excerpt will be published in full in the Northern Colorado Writers Anthology, Spring 2023, a collection dedicated to the theme of “Exception/All: An Exploration of Normal"

In June 1967 Pete learned he had been selected for a summer job in California with the Student Health Project, a federal anti-poverty program. He asked and I said yes and watched him move into action. Pete was the great planner, the great provider, controller, idea man, with notes on index cards in his pocket and boxes of loose change on the dashboard. We had to get to California soon. But where to get married? The District, where I lived, had a waiting period for blood testing; Virginia, where Pete lived, prohibited interracial marriage. The laws of slavery had written that one-part Negro blood meant you were the master's property, and Jim Crow titrated blood along similar lines.

The New York Quarterly in 2022.

I wrote this poem in response to a prompt given by poet Carolyn Forche in a Lighthouse Writers workshop focused on the poetry of witness.

To wander East Colfax Avenue in the 1970s is to be young, female, angry and ripe, a June tomato planted early, reddens on the vine, splits open and bleeds. It runs down your leg and stains the street. You don’t stop, you don’t wipe, you let it remain, to remind us of the disappeared women, to remember Joan Little, the inmate who refused the guard in the prison kitchen with an ice pick.

Nominated for Best of the Net 2020

The look he’s giving Nancy says to me it’s more than land he craves. And not just her beauty, he told me in private, but it’s something else in her that he needs. “Not the way a drunk needs a drink, Father,” he explained, “or the way a child needs a mother, more like a sinner needs a priest.”

Colorado Book Award-Literary Fiction, Finalist

My Sisters Made of Light is a novel set inside Pakistan’s human rights movement, 1957 to 1994. The story follows three generations of a Pakistani family as they make their way through life in the political, social, and religious maze that is their motherland. This novel pulls readers into the fascinating, heartbreaking, and often terrifying world of honor crimes against women in Pakistan through the life and family history of Ujala, a dedicated teacher. When Ujala decides to follow the path her mother has prepared for her, she pushes aside fears to help other women escape from impossible situations.

AN EXCERPT FROM THE NOVEL:

In 1958 the air was still sour with the stench of the slaughters that had occurred eleven years earlier when the British ran like dogs and India cracked. The blade that slashed the map also partitioned the bodies of the people, etching fear in their bellies and revenge in their hearts. Ten million people migrated. Lines and lines of Hindus from the Indus River Valley, in what would later be designated “Pakistan,” packed their lorries, rode bullocks, and walked, to cross the border into India. Lines and lines of Muslims from India carried all that they owned to be part of the new Islamic nation. Rioting occurred first in Calcutta and then spread to Punjab. The refugees scouted the routes to avoid one another in the passing. If a trainful of Hindus was murdered by Muslims from Lahore (and they were), then a trainful of Muslims would be murdered by Sikhs and Hindus from Amritsar (and they were). Entire families were butchered and their body parts were delivered by horseback to their villages. The people emptied baskets of breasts and pails of penises onto the ground—even the stubs of baby penises with scrotums like tiny figs. The soil was soaked with all the lost futures, and when it was done, when the trauma finally subsided to abide in the bodies of the people, they had to plant seeds in, and eat the fruit of, the same earth. Sikhs and Muslims alike knew the taste of each other’s blood well, and they kept to their own.

Kulraj and Nafeesa in London. Romeo and Juliet in Verona. A Muslim and a Sikh in Pakistan. All of history conspired against them, but no matter. They would find a new way.

Sage Green Journal (http://sagegreenjournal.org/jacqueline-st.-joan.html)

I

I drive the canyons of the West

Deliberately,

The way I drag my finger between

The shoulder blades of the cat.

Third Place, The Colorado Lawyer Poetry Contest, 2006.

If you ever get the chance, live with an artist.

Live with an artist and you begin to notice

the shapes of things.

Even the air around the enormous

sprig of forsythia

in the beer bottle,

the way its presence

makes the room fade away,

its relationship with the white wall,

its simple canvas.

First Place, The Colorado Lawyer Poetry Contest, 2006.

I am watching the freckles

on the back of my fingers

multiply and divide like

lovers under the lens. The

speaker at my podium

says: He's my pimp. Tore

a branch from a tree. Beat

me. The branch broke.

Honorable Mention, The Colorado Lawyer Poetry Contest, 2006.

Although it is summer evening,

hair spray and Nescafé

smell so strong and familiar

it makes one wonder if it is morning or night.

In the tiny yellow bathroom,

From Empire Magazine, The Denver Post

It is a world of birds here in the morning. Busy magpies with sticks. Occasional duck couples settle into the lake. A thousand starlings fill the empty branches of an enormous poplar. When I look up at the tree again, and the black birds have all departed without a sound, without a trace. I am stunned. I grieved the whole year my last child left home. When I dream at the change of seasons, it is often about them as little children, as they were then, sleek and wild, our life full of surprise and struggle. In the dreams we are together again, as if they arrive and depart from me regularly due to the energy and excitement of the equinoxes. All the seasons of my life circle around and I can be all ages.

Memoir Excerpt

A journalist once asked me how I’ve managed to overcome so much in my life. The question stunned me. It had never occurred to me that I had overcome anything. I was just living my life. What she was referring to, of course, was that, compared with many judges, my life has been unconventional. A working class background. Interracial marriage. Welfare mother, Feminist. Community activist. Bi-sexuality. Poetry. What bothers me about the question is the idea of overcoming something, as if I had to conquer my own life, when this life I’ve been making has also been making me. I am a part of so many of the extraordinary, ordinary events and people in court. People like myself, who try to face life and need a little help doing so.

Winner of the Silver Solas Women's Travel Writing Award, 2009

The best account by a woman of an encounter or experience on the road.

My first impression of Lhasa is the ubiquitous, identical white-tiled buildings that the Chinese government builds to line the streets, hiding even the grand Potala Palace from our view. Our hotel, although modest, feels like a palace to me. The entrance is beautifully flowered and we have our first sit-down toilet.

Published in Mountain Talking, Fall, 2016 and Sage Green Journal

It is a beautiful thing to wake

in the dark chill of October

and go out into it

where a crescent moon

and two stars appear both ahead

Published in The Denver Quarterly

There's a dead baby in your yard

the newsboy said when he knocked on the door.

It was over by the fence. It was naked. It was blue.

It was bloody placenta all over the ground

and red spots on the fence. Red spots on the fence

Denver Press Club Poetry Award

Your poems shock

the way waterlilies burning in a museum

shock the moneyed. With fragrant treason you begged even the rich,

to understand, As you spoke to each generation as that generation,

your dark hair curled in the thirties

by a passion electric for justice.

First Place, Lyrical Poetry, Columbine Poets of Colorado, 2015

He says, What’s the biggest number?

What’s out there, after atmosphere and space?

We are driving home from preschool.

There is no biggest number, I say.

There is always one more.

Turkey Buzzard Press

Vees of geese are sewing Denver back into its morning,

where telescopic, multifaceted periscopes

take in the entire dance & climb.

To the west, snow- peaked triangles; downtown,

rectangles of finance & domes of government;

under the interstate, warehouses of industry &

puffs of cottonwood along the river.

This “family fiction,” won the 2019 Black Sheep Award of the Colorado Genealogical Society

In those days I’d take the train from Union Station in Denver, my home town, to Union Station in Washington, D.C., where the reporting work was. It took a couple of days, but it gave me time to do some writing in the dining car that had a quiet bartender, and to watch the country roll by. There were hobo camps along the rails--you could tell by the smoke. I could take a close up look at them and then roll on by, settle back, open a book or pick up a pen.

Second Place, Free Verse, Columbine Poets of Colorado, 2016

I love the margins,

the left margin

that anticipates comment,

leaves room for

corrections, doodles,

Published in Texas Journal on Women and the Law

A measure of justice

40 pounds weighed on the public scale

the child's eyes

look down at his heart for mother.

It's Charleston. 1815…

Novel-in-progress

What must it be like to have a sister, to be close to a sister, to share everything, then to lose her, to not want to believe that she is dead, to be separated so long that you might pass each other on the street and never notice? To lose her so long ago you only wonder occasionally if she is in good health, if she still lives. You forget what her voice sounds like, or believe you have forgotten because you cannot bring it to mind. What did she sound like? But then a miracle happens and years later when you are no longer young, no longer full of the possibilities of youth, but instead you are coasting on the remains of a lifetime of experience, and you hear a stranger’s voice ask, “May I help you?” and you know at once whose voice it is. You know the shape of the face, the dimple, the particular smile of those particular lips. And you recognize the light in the eyes of your sister.

Feminist Legal / Literary Anthology of Poetry & Fiction published by Northeastern University Press

By suggesting that women lawyers move beyond Portia, the traditional patriarchal symbol of female perfection in the law, we hope to encourage the invention of new paradigms that will split open our thinking about these questions and move us beyond the binaries of male/female, insider/outsider, rights/caring, and justice/mercy.

Published Online, Rename St*pleton for All

White people can’t change the story of our collective past, but we can influence the ending. For us to take responsibility for dismantling white supremacy, we must

Know white history—both collective and personal-- so we understand and are not surprised to learn of its impact on communities of color.

Explore white privilege-- how we benefit directly or indirectly.

Own that shameful history. It belongs to us even though we wish we did not

Disown white supremacy completely. Try to undo the damage it has caused.

Memoir Excerpt

In the field of reverie I am wise and wordless. The urge toward words is small and moves quietly, simultaneously with all else that cannot be named.

Article Published in The Coloradan

One little boy is especially scared and crying loudly. It is difficult to tell how much of his distress is physical pain and how much is fear. The noise increases tension in the room, but the professionals keep to their tasks. We worry that the boy’s screams will frighten the waiting children. “This is when you need a clown,” I say to Laurie.

Special to The Denver Post

At the Arlington County Courthouse, they asked about our bloodlines, and in the box marked “race,” Pete wrote “B” for black. I wrote “H” for human.

Finalist, F(r)iction Spring Short Story Contest, 2016

I passed the entrance to Chitral Gol, the wildlife sanctuary where snow leopards hunt horned goats. A tree sparrow and a whistling thrush sang on the holly oaks on the cliff. In a field of snow-covered rhubarb, a pair of partridges called back and forth in staccato, as if I were a wild cat they were warning other birds. Crows swarmed as one body, cawing their criticisms wildly. Who is she? What is she doing? Why is she alone? Where is her husband?

Published in Thinking Women: Introduction to Women’s Studies, Kendall-Hunt, 1995.

I watch you in the court

House coffee shop. Sitting next to

The angry young woman. The one with

A newborn tied to her chest. Fear

And despair criss-cross her back. You…

Published in War, Literature and the Arts, 1997 and in Thomas J. Cooley Journal of Clinical and Practical Law, 2001. It won a Clincal Legal Education Association poetry award.

Glenn Miller was missing. Somewhere over the English Channel,

his plane went down in December 1944. You'd been drafted,

even with a wife and two daughters to support and

day work in a defense plant and night work in the clubs,

your teeth clamped onto the reed of a saxophone, chin tucked in…

F Magazine

Brick Factory, Punjab, Pakistan

Literacy Class Graduation

After the custody hearing

Child trash pickers in Karachi

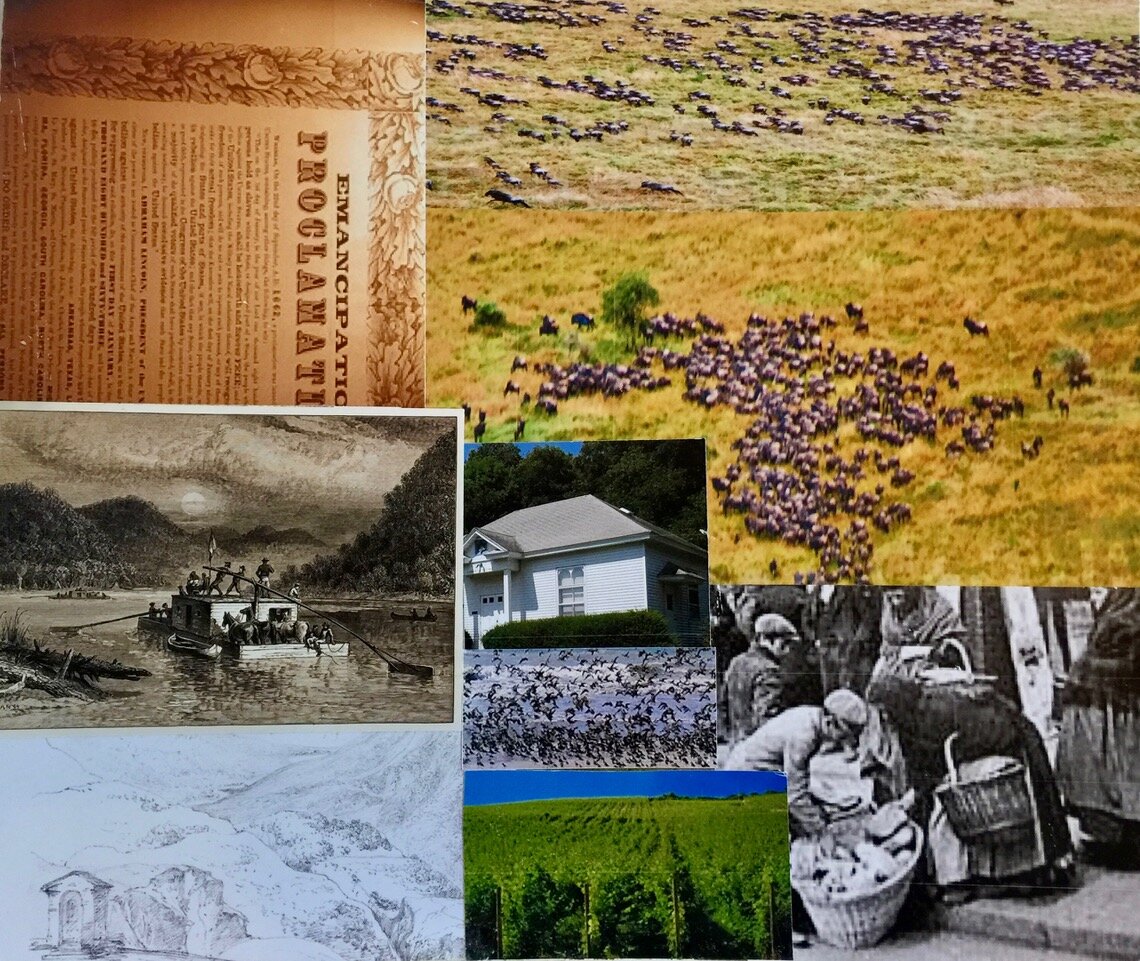

“How they traveled” collage by Jackie

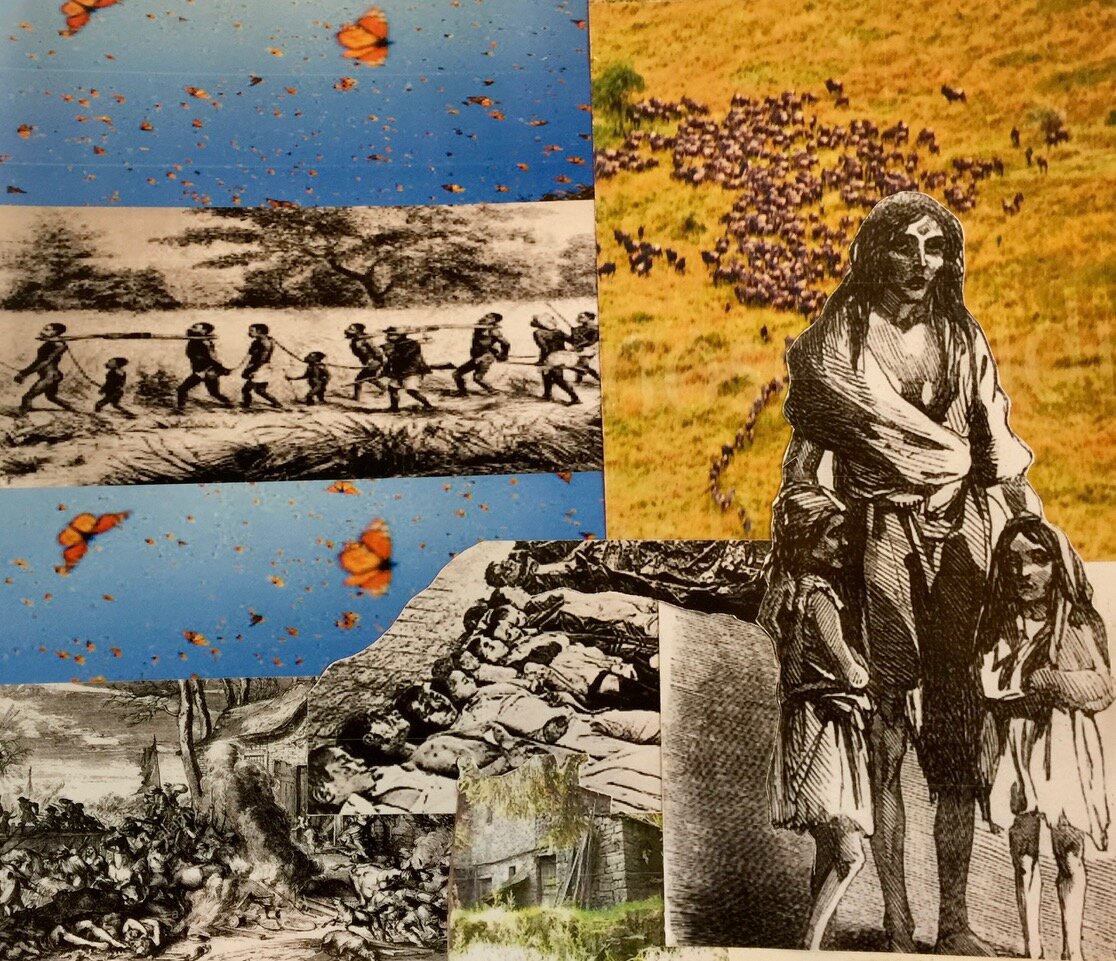

“Why they left” collage by Jackie